Serving Those Who Served

Catholic Charities Programs Empower Veterans on the Homefront

By Julie Bourbon

One client had been homeless for decades and didn’t know he was owed 40 years of VA benefits. Another became housed after living in a tent on the shore of Lake Michigan. And yet another is living in supportive group housing and working on his master's in social work so he can help fellow veterans turn their lives around as he has.

Catholic Charities staff who work with veterans have stories to tell of those who’ve served their country — many in dangerous, traumatizing circumstances — only to find that life out of the service can be fraught with daily peril of another kind: debt, homelessness, mental health crises, substance use disorders and piles of paperwork that would overwhelm the most organized and well-adjusted among us.

Their needs run from the benign to the acute, and those who land on the doorstep of a Catholic Charities agency often find community and new purpose at residential facilities and drop-in centers that offer case management, housing and referrals for services ranging from medical to legal to financial. But first they must do the one thing — ask for help — that service providers say doesn’t come easily to this population.

Purpose and Self-Sufficiency

Ezra, the Liberty House therapy dog, is a very good boy, posing with Executive Director Jeff Nelson, far right, and several donors.

Ezra, the Liberty House therapy dog, is a very good boy, posing with Executive Director Jeff Nelson, far right, and several donors.

Patrick Shiflett, a Liberty House resident, with staff Ashley Kitchell, left, and Stephanie Murphy, attend an event celebrating the program's 20th anniversary.

Patrick Shiflett, a Liberty House resident, with staff Ashley Kitchell, left, and Stephanie Murphy, attend an event celebrating the program's 20th anniversary.

Liberty House is a residential, sober-living facility that accommodates up to 18 male residents and calls itself an “action-oriented, transformational” four-step program that begins with rediscovering purpose.

Executive Director Jeff Nelson has been with the Manchester program since before it became part of Catholic Charities New Hampshire in 2019. He’s one of a staff of four, including two case managers — plus Ezra the therapy dog — and says getting vets to seek assistance can be half the battle.

“There’s a stigma still in the military around getting diagnosed, number one, and number two, leaving your unit and feeling as though you let people down that you care about,” he says. Still, more than 110 men applied last year.

Participants start by creating an action plan with a case manager once they’ve been accepted. That includes financial counseling (for issues such as credit card debt and overdue child support), restoring driving privileges (which may entail dealing with departments of motor vehicles in multiple states), determining if they’re eligible for VA benefits (not all veterans are — some must apply for Medicare or Medicaid, instead) and obtaining documents (such as Social Security cards and birth certificates) — fairly typical issues for veterans, says Nelson.

Once employed, residents give Liberty House half their earnings to put in savings, for when they leave. After six months, they pay 20% of the other half, “as an administrative fee, just so they have a little skin in the game here,” says Nelson, noting that most save between $5,000 and $10,000 over a year.

The men eat dinner together, attend weekly drug and alcohol counseling group sessions and take part in outings, such as baseball games, bowling or deep-sea fishing trips. “Mandated fun,” Nelson calls it.

Patrick Shiflett, a boyish 38, is in his second stay at Liberty House. He left the military in 2019 after 16 years, including tours in Iraq and Afghanistan. Two years ago, he realized he needed rehab and flourished at Liberty House but stumbled after leaving.

“I kind of got lost in transition and wound up needing extra support. So, before I lost everything, I raised my hand and asked for help, and they took me right back immediately,” says Patrick, who plans to start a master’s in social work soon, to counsel other veterans.

“It’s a place that if you want to get back on your feet, it’ll 100 percent happen, and nothing but love here.”

Nelson and his staff also see about 450 veterans each year for non-residential services, such as food, clothing, toiletries, bus passes and the occasional gas card. These visits almost doubled in 2023, to 2,800, with more women and older vets than ever before. Nelson blames the economy and high housing costs for the uptick.

Building Camaraderie

Providers in other states are seeing the same trends. MANA House, a program of Catholic Charities Community Services Arizona in Phoenix, provides temporary housing to as many as 76 male veterans experiencing homelessness. With the high cost of housing in the Phoenix area, more and more older veterans, many from the Vietnam era, are ending up unsheltered.

MANA — Marines, Army, Navy, Air Force — operates on a housing-first model that does not make a prerequisite of sobriety, says Program Director Danelle King. Men are referred through the VA, which has a national coordinated entry system to connect homeless clients to care and services.

“A lot are on fixed incomes,” she says, and can’t afford their rent anymore. They’re also staying longer at MANA than the previous norm of three to six months; residents may stay for nine months or more now. “Because they’re up there in age, they’re having issues with taking care of themselves. Whether they have mobility issues, memory issues, whatever the case, they need a little more assistance.”

For some, that next stop will be assisted living, because MANA is not equipped to provide extra assistance, such as bathing and dressing. That’s what happened with the man who’d been homeless since Vietnam and recouped 40 years of benefits with MANA’s help. Staff connect clients to Supportive Services for Veteran Families (SSVF) or HUD VASH (Veterans Affairs Supportive Housing), both federal programs, to arrange long-term housing.

“We are held accountable to making sure that when we exit that person, they are ready to go as much as our program is able to help them get there.”

MANA accepts any male veteran other than those dishonorably discharged. The men live four to a room and are provided three meals a day, which they typically eat together. A case manager conducts a weekly recovery group, although participation is not mandatory.

King, an Army veteran, notes that the men have light chores to perform, which hearkens back to the military culture they are already familiar with and helps to build camaraderie. Those relationships have paid it forward on at least one occasion that she can recall, when a former resident started his own business and hired MANA House veterans to work for him.

“It does go back to that shared past of being in the military,” she says of the bonds that creates. “It’s something we’ll always relate to each other on, even if everything else about us is different.”

Staff and residents of MANA House are devoted Arizona Cardinals fans and attended a game courtesy of a generous sponsor.

Staff and residents of MANA House are devoted Arizona Cardinals fans and attended a game courtesy of a generous sponsor.

Local seminarians regularly volunteer at MANA House in the donation room, dining hall/kitchen and dry goods storage area.

Local seminarians regularly volunteer at MANA House in the donation room, dining hall/kitchen and dry goods storage area.

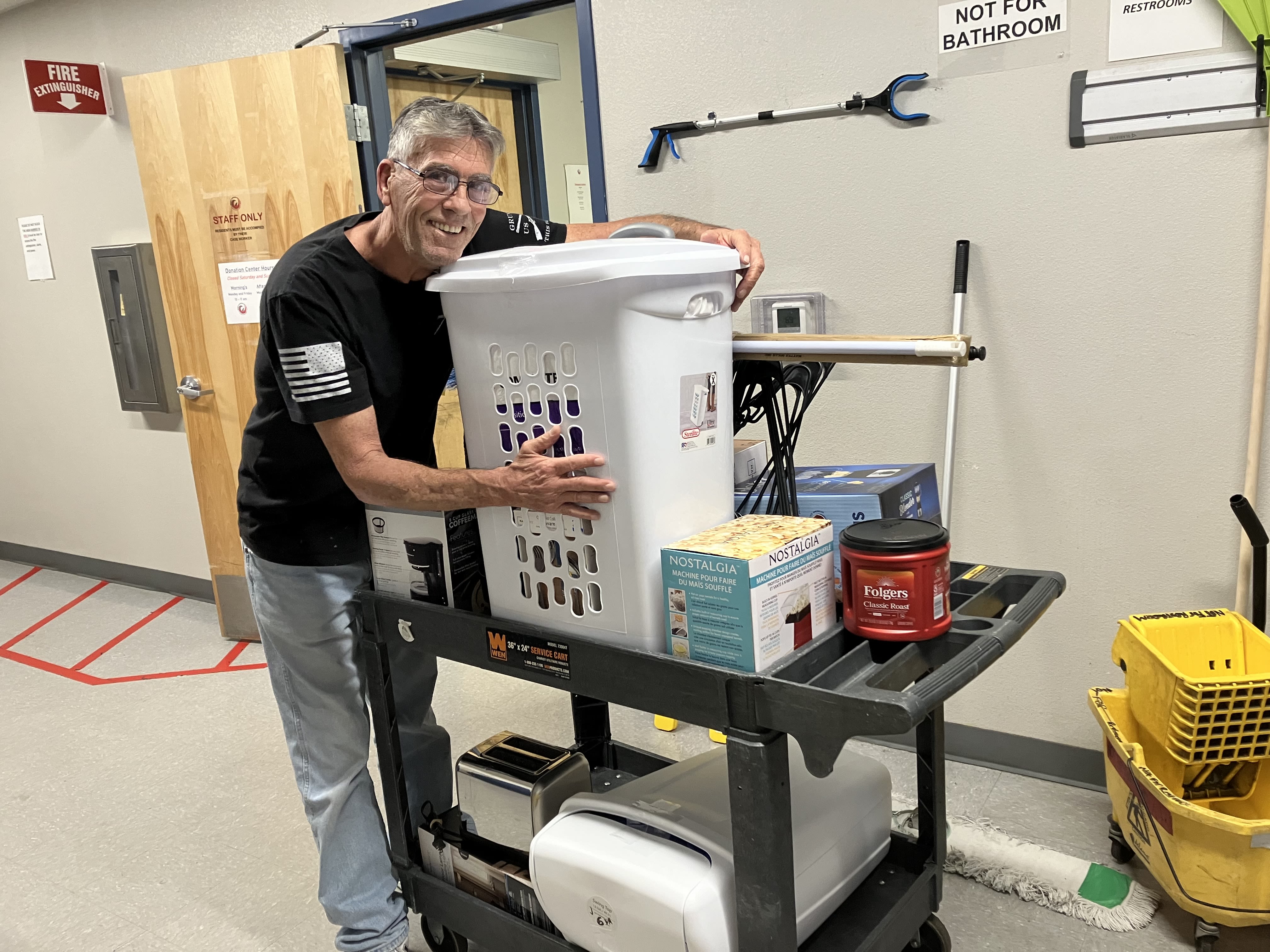

Veteran Arthur Roth graduated from MANA House in January 2024 and was gifted with supplies to get him started in his new apartment.

Veteran Arthur Roth graduated from MANA House in January 2024 and was gifted with supplies to get him started in his new apartment.

One of MANA's partners provided them with cleaning and hygiene supplies, pillows, sheets, towels and underwear for residents.

One of MANA's partners provided them with cleaning and hygiene supplies, pillows, sheets, towels and underwear for residents.

'Vulnerable Heroes'

Resident of St. Leo's meet for a community presentation in a common area on the campus.

Resident of St. Leo's meet for a community presentation in a common area on the campus.

In the middle of the city, the St. Leo Veterans Garden is a peaceful spot for residents to gather outside.

In the middle of the city, the St. Leo Veterans Garden is a peaceful spot for residents to gather outside.

The St. Leo's campus was built on the site of an old Catholic parish in the heart of Chicago's South Side.

The St. Leo's campus was built on the site of an old Catholic parish in the heart of Chicago's South Side.

St. Leo Residence for Veterans opened on the site of an old parish in 2007 as a joint venture between Catholic Charities, HUD and the VA, the first of its kind in the nation. A permanent supportive housing program of Catholic Charities of the Archdiocese of Chicago, it can serve up to 141 veterans, both men and women, in studio apartments with access to common areas including a fitness room, library and laundry facilities.

There is no limit to how long residents can stay, but the average is four to five years. Depending on the funding source for the veteran’s subsidy, they may pay 30% of their income as rent — roughly $138 to $350 per month — although having income is not a prerequisite to live there.

St. Leo’s four case managers connect residents to educational and food resources; transit, employment and legal services; health care; drug and alcohol counseling; and public and VA benefits. Residents — who are regarded as “vulnerable heroes” by the staff — are asked to meet with their case manager twice monthly to update goals and accomplishments, but they’re not required to partake of services or to be drug-free.

“Someone’s reluctance to engage in services is not going to stop us from doing what we’re here to do, because our responsibility when we walk through the door every day is to make sure that our residents are safe and that we are there to assist them to become whatever type of person they want to become,” says David Dempsey, St. Leo’s director. “We use a housing first/harm reduction philosophy, to meet residents where they are so they can improve the quality of their own living and get to a place where they want to be, where they’re happy and safe and reaching their goals.”

Audrey, 62, had been at St. Leo for three years. An Army veteran, she was previously living in a tent encampment along Lake Michigan and had difficulty navigating the VA system. Now her case manager helps with her VA and transit benefits, and she’s received assistance for her substance use.

“There are staff to talk with whenever you need to who really care, and there are other veterans to talk with who share similar experiences,” she says, with a regret that she didn’t get assistance from St. Leo's sooner. “Veterans need to seek out services and be told about services available to them.”

The majority of residents are over 62 and increasingly require additional help due to chronic health issues and dementia; some will ultimately have to leave for a residence that provides a higher level of care than St. Leo's can accommodate. For all residents, the program is meant to provide supportive services necessary to remain housed.

“One of the main goals is to promote self-sufficiency so that people can get to the point where they don’t need the services to remain housed.”

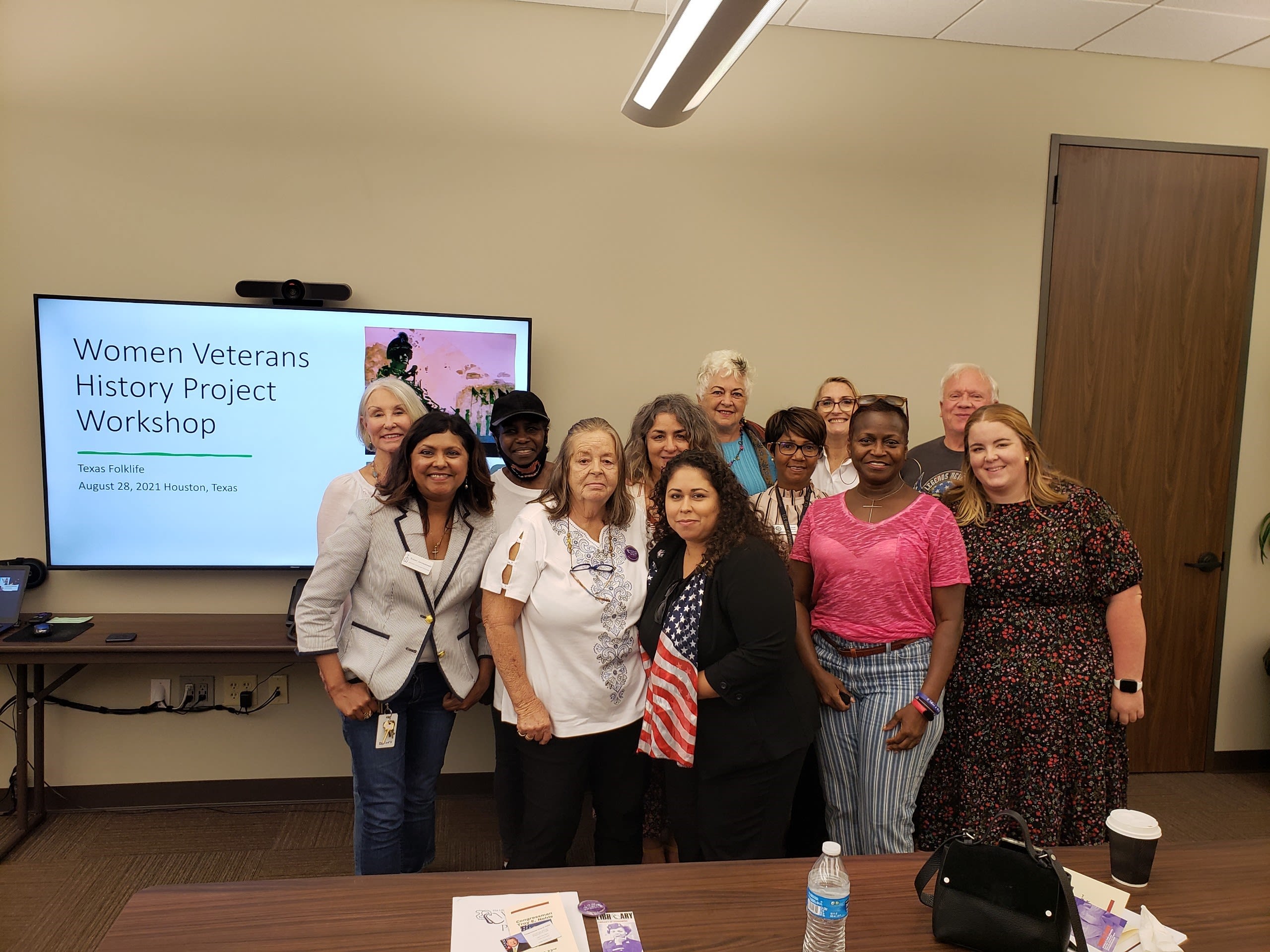

For Women, Hope

Last year, Pathways to Hope, the women veterans program sponsored by Catholic Charities Archdiocese of Galveston-Houston, served more than 100 clients through online weekly peer support calls, emergency shelter, mortgage/rental assistance, food pantry, even equine therapy. Veterans may come one time or for half a year or a year, says Susan Jaroszewski, senior case manager.

Pathways to Hope was once a residential program — between the pandemic and budgetary issues, they recently closed a 26-bed facility — and housing remains one of the primary needs the staff sees among clients, as does food assistance.

“When they come in for the intake, I usually give them a box of food. That’s just standard operating procedure,” says Jaroszewski, who is currently the only case manager on site, down from a high of 10 to 12. She is busier than ever. “We are slammed with requests. We got a call from Atlanta, Georgia, last week, but we’re only assisting clients in the Houston area.”

Women in need of housing are usually sent first to a hotel while they wait to get their HUD-VASH voucher for permanent housing, and women with children get priority. Then they have to find an apartment they can afford. Financial coaching comes in handy here, says Jaroszewski.

“A lot of veterans, they used to get a paycheck every four weeks. They never really learned to budget, or never had to, so when they get back to the civilian life, they don’t know how.”

That was true for Yolanda Winston. Now 48, she’s retired on disability after 23 years in the Air National Guard in Arkansas, a painful separation that included legal battles to get the benefits she believed she was entitled to. She moved to Texas in 2023 for a fresh start and ended up in line at a food pantry.

“I asked for help. I didn’t have any resources, I was tired and needed to heal,” she says. Pathways to Hope helped her with housing, utilities, bills and budgeting. Winston took part in as many services as she could — grooming horses, participating in career and life coaching and taking leadership classes.

“That gave me a sense of belonging. They helped me get stable.”

Winston now feels financially and personally settled, but still logs on for the weekly peer-to-peer call and attends group events, relishing the community she has formed there. That’s a win, as far as Jaroszewski is concerned.

“Our goal isn’t to keep them here and keep them in the same cycle,” she says. “We want to empower them.”

The Women Veterans Program sent 104 Christmas care packages to deployed troops in Romania, Poland, Kuwait, Lithuania and on the USS Eisenhower.

The Women Veterans Program sent 104 Christmas care packages to deployed troops in Romania, Poland, Kuwait, Lithuania and on the USS Eisenhower.

Pathways to Hope clients attended an empowerment expo in Houston with about 130 other women veterans.

Pathways to Hope clients attended an empowerment expo in Houston with about 130 other women veterans.

Participants in the Women Veterans Program attended a festive Galentine's Day dinner at a Houston restaurant.

Participants in the Women Veterans Program attended a festive Galentine's Day dinner at a Houston restaurant.

2050 Ballenger Ave, Suite 400

Alexandria, VA 22314

703-549-1390 | catholiccharitiesusa.org

© 2024 Catholic Charities USA. All rights reserved.

Terms of Service | Privacy Policy

CCUSA is a 501(c)(3) non-profit organization.

Federal Tax ID Number 53-0196620